By Ken Lizotte CMC

As part of his ongoing column in Money Inc.

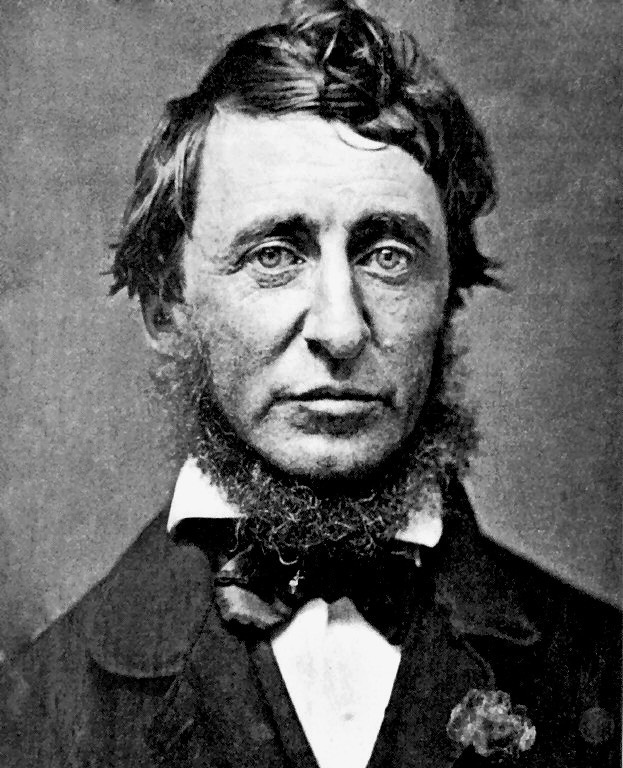

Many of life’s major arenas and how we approach or practice them, such as environmentalism, writing, travel, war and peace, politics and rebellion, philosophy and introspection, are steeped within the life and legend of Henry David Thoreau.

Thoreau’s studies of nature for example, conducted without the slightest aid of today’s body of science or available technology, continue to serve as the underpinning for such events as the annual spring nature census at Walden Pond where environmental scientists and other naturalists gather every year to survey the effects of climate change on plant life. And Thoreau’s 1849 essay on civil disobedience has influenced millions over the course of more than a century and a half since he first penned it, including the likes of Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Frank Serpico, FDR and the anti-war protesters of the 1960s.

But despite all this notoriety in so many significant life categories, one segment of Thoreau’s contributions that has been little explored is his impact on business. As an uber-independent personality who spent so much of his adult live indulging in his curiosity and passions to the exclusion of a trade or career, Thoreau’s business contributions have been passed over by historians and wide-eyed Thoreauvians alike, to the point of provoking chuckles today at the mere suggestion. Many scoff at even the notion of the b-word belonging in the same sentence with Henry’s name.

But there is indeed a case to be made in terms of business milestones achieved by Henry Thoreau in his lifetime. As a result, a number of lessons his insights offer us are worth to paying attention as we strive to attain our own business goals. Here are four worth contemplating:

1. When founding a business or embarking on a profession, envision what you want, believe in it, then go after it. In our modern era, companies are continually told to formulate a “vision” or mission statement in order to know where you’re going. But too often the path to such a vision/mission is traveled in a backwards direction by trying too hard to be practical, reasonable or careful. In a dog-eat-dog world, hard-nosed pragmatism is the only sensible approach, they insist.

Yet leading thinkers disagree, particularly those who have upset previously long-assumed apple carts to create such astonishing breakthrough business models as Amazon, Starbucks, Apple, Google and Uber. They adhere to Jim Collins’ landmark advice to set “big hairy, audacious goals” as well as to Thoreau’s own dictum “If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be,” adding, “now put the foundations under them.

2. When confronted with a problem, research your way to a solution. Henry Thoreau acclimated to business at an early age, growing up amid his father’s pencil factory. Studying at Harvard however he had chiefly immersed himself in the classical literature as well as Greek, Latin, Italian and other languages. So upon returning home after graduation, one might assume that such an academic focus afforded him little or nor preparation for a career in the family business. But just the opposite proved true.

Pencil manufacturing in the US at the time was extremely competitive, with many pencil “products” lacking the reliably fine-point consistency we are accustomed to today. So inspired to uncover a solution to this, Henry took himself back to Harvard for a week to engage in an MBA-like “independent study” project, specifically aimed at how to fashion a “recipe” for pencil lead that would transform Thoreau pencils into an efficient product that everyone could use and love.

Drawing on his Harvard-acquired study and research skills, he soon located a solution that in fact had already been put into practice in France. It was well-known that pencil factories there had found a way to regularly churn out high-quality pencils composed of a precise formula of high-quality graphite and clay that facilitated writing and drawing characterized by predictable neatness and legibility. The discovery, plus Henry’s additional improvement of the pencil’s point, elevated Thoreau pencils to the top of its industry. Over time, American pencil-makers as a whole were able to join those in Europe in transforming this utensil into an instrument of communication that solidly left the inkwell and quill far behind.

3. Measure what you can by keeping records. Another widespread misconception of Henry David Thoreau is that his naturalism bent was so anathema to materialism that the mere mention of numbers and bookkeeping would send him sauntering quickly back into the woods. Yet when visitors to Walden Pond pass by a replica of the one-room cabin he had built there in the mid-19th Century, they also encounter a plaque commemorating the painstaking accounting he made of each and every cost involved in his little building project. To whit:

Board’s: $8.03 1/2, mostly shanty boards

Refuse shingles for roof and sides: $4.00

Laths: $1.25

Two second-hand windows with glass: $2.43

One thousand old brick: $4.00

Two casts of lime: $2.40. That was high.

Hair: $0.31. More than I needed

Mantle-tree iron: $0.15

Nails: $3.90

Hinges and screws: $0.14

Latch: $0.10

Chalk: $0.01

Transportation: $1.40. I carried a good part on my back.

In all: $28.12 ½

Thoreau ends with this notation: These are all the materials excepting the timber, stones and sand, which I claimed by squatter’s right.

4. When running a business do it your way — even at the cost of failure! A “Thoreau School” in Thoreau’s hometown of Concord, Massachusetts, founded and managed by Henry and his brother John, defied many of standard education principles of that time. Rote memorization, for example, was out as was corporal punishment. Instead the vision of the brothers’ school was based in such humanistic principles as building character, encouraging innovative thinking, and instilling a love for life-long learning.

Though the Thoreau School thrived for many years, it ran out of steam ultimately and closed down. Some have attributed its death knell to its unorthodox approach but if this was the case, the founders apparently had no regrets. To force themselves to upend their values for the sake only of profit and solvency would have undoubtedly left them unfulfilled. Yet over one hundred fifty years later, their notions for running their business are now the accepted norm. We thus owe a debt of gratitude to Henry and John Thoreau for doing it their way or not at all.

The world of business can therefore be justifiably added to the long menu of so many life endeavors influenced by the ideas of Henry David Thoreau. By recognizing this reality, we can place his independently arrived-at concepts under a microscope and benefit here too from this iconoclast’s perspective. Doing so will surely enable many of us in business to guide our own business lives to ever higher levels of success in terms of prosperity and career fulfillment.

Ken Lizotte CMC is Chair of the CEO Club of Greater Boston, and Chief Imaginative Officer (CIO) of